Old Testament Imagery in Revelation: Daniel, Ezekiel, and Isaiah

Quick Summary

Revelation draws heavily on Old Testament imagery, especially from Daniel, Ezekiel, and Isaiah. Daniel contributes visions of beasts and thrones, Ezekiel offers temple and prophetic imagery, and Isaiah provides language of judgment and hope. Together, these references root Revelation in God’s earlier promises while pointing toward Christ’s ultimate victory.

Introduction

Revelation is not a stand-alone book dropped from heaven. John doesn’t invent his visions from scratch. Instead, he writes with the paintbrush of the Old Testament, dipping again and again into the colors of Daniel, Ezekiel, and Isaiah.

This isn’t simply quotation. Revelation never directly cites the Old Testament the way Paul does. But everywhere you turn, the language and imagery of the prophets surface. To read Revelation well, you have to read it with the Old Testament in the background.

Why does John do this? Because God’s promises are not new inventions. They are the continuation and fulfillment of what has already been spoken. Revelation is the climax of a story that started long before Patmos.

Daniel: Beasts, Thrones, and Son of Man

If you’ve ever read Daniel and then moved straight into Revelation, the echoes are impossible to miss.

Beasts Rising from the Sea

In Daniel 7, four beasts rise from the sea, each representing kingdoms of the earth. In Revelation 13, John sees a beast rising out of the sea, a composite of Daniel’s beasts. John isn’t simply borrowing imagery—he’s saying Rome and its powers are the latest in a long line of beastly empires. What Daniel saw in fragments, John sees fulfilled in his own day.

The Ancient of Days and the Throne

Daniel 7 also gives us a vision of the Ancient of Days, seated on a fiery throne, with books opened for judgment. It’s a scene of overwhelming majesty, where God’s sovereignty over history is beyond question. Revelation picks up the same imagery when it describes the great white throne in Revelation 20. John paints with Daniel’s palette of judgment and sovereignty, showing us that the God who sat enthroned in Daniel’s vision is the same God who presides at the end of all things.

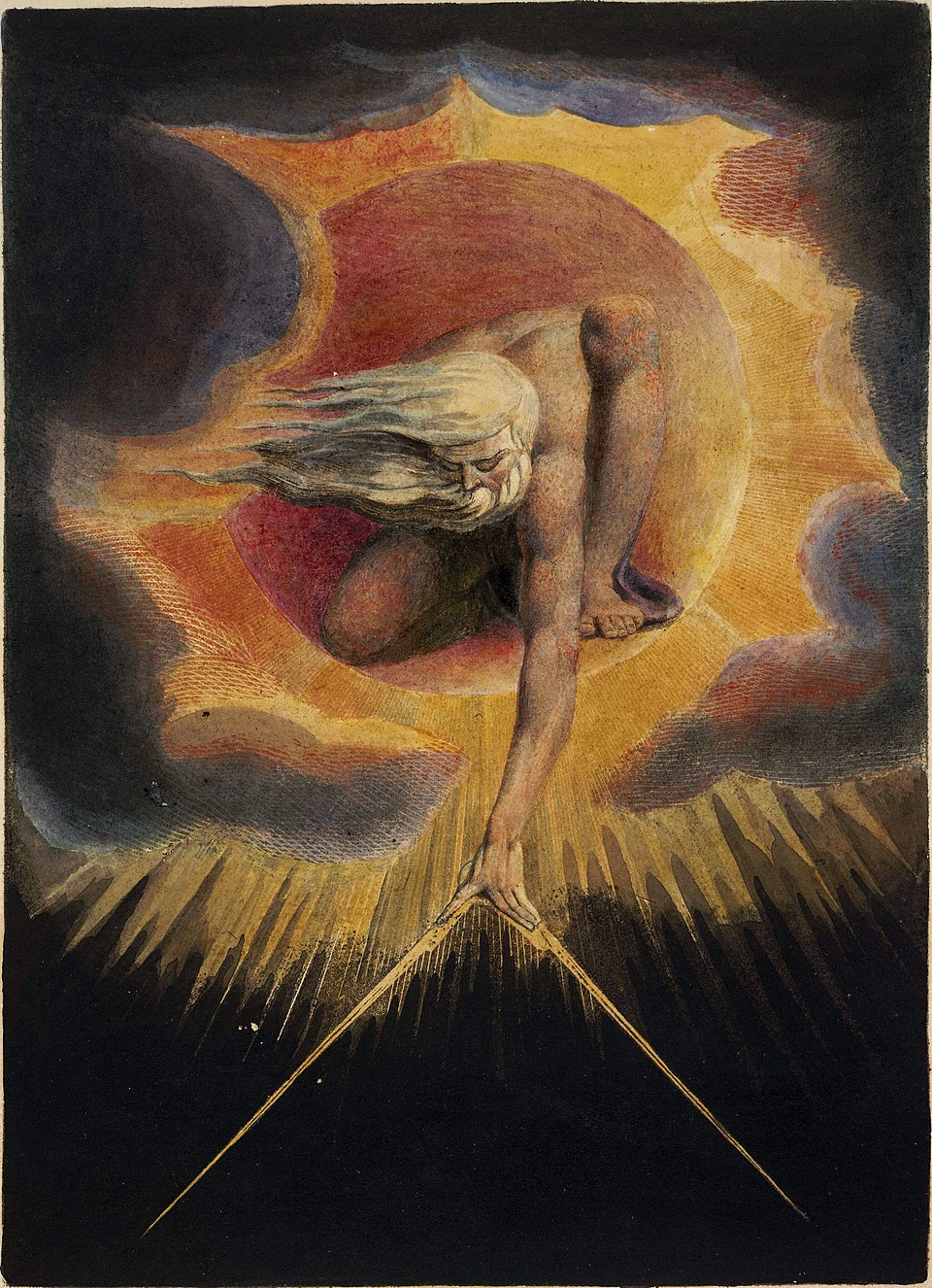

Artists across centuries have been moved by Daniel’s image. William Blake, for instance, painted a striking work titled The Ancient of Days, capturing in vivid color the mystery and power of the figure Daniel described. John’s vision in Revelation echoes that same majesty: the throne of God blazing with authority, ruling over every empire and age.

Artists across centuries have been moved by Daniel’s image. William Blake, for instance, painted a striking work titled The Ancient of Days, capturing in vivid color the mystery and power of the figure Daniel described. John’s vision in Revelation echoes that same majesty: the throne of God blazing with authority, ruling over every empire and age.

The Son of Man

Daniel 7:13 describes “one like a son of man” coming with the clouds of heaven, receiving authority and kingship. Revelation 1 portrays the exalted Christ in similar terms—hair white like wool, eyes like fire, standing among the lampstands. John shows that the Son of Man Daniel foresaw has now been revealed fully in Jesus.

Have you ever wondered why Jesus is called both the Son of God and the Son of Man? Read more here.

Ezekiel: Prophetic Vision and Temple Imagery

If Daniel gives Revelation its beasts and thrones, Ezekiel gives it much of its texture.

The Scroll and the Prophet’s Call

In Ezekiel 2–3, the prophet is given a scroll to eat, filled with words of lamentation. In Revelation 10, John receives a little scroll from the mighty angel and eats it. Both scrolls taste sweet but bring bitterness. The prophet must speak God’s word even when it means hardship.

The Measuring of the Temple

Ezekiel 40–42 contains an elaborate vision of the temple being measured. John echoes this in Revelation 11, where he is told to measure the temple of God. The imagery shows God’s care for his people—the temple is secure even when the outer court is trampled.

The River of Life

At the end of Ezekiel (ch. 47), a river flows from the temple, bringing life to the land. Revelation 22 picks up the same picture: the river of life flows from the throne of God and of the Lamb. Ezekiel’s vision of renewal finds its climax in John’s vision of the new Jerusalem.

Isaiah: Judgment and Hope

Isaiah’s fingerprints are all over Revelation, especially in the contrasts between Babylon’s fall and Jerusalem’s restoration.

The Fall of Babylon

Isaiah 13–14, 21, and 47 all speak of Babylon’s arrogance and downfall. John takes those oracles and applies them to Rome in Revelation 17–18. The harlot clothed in purple and scarlet, the city fallen in a single hour—it all rings with Isaiah’s prophetic tone.

The New Heavens and New Earth

Isaiah 65–66 promises a new heavens and a new earth, where sorrow and weeping will cease. Revelation 21 opens with the same words: “Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth” (Revelation 21:1). John doesn’t invent the hope—he confirms it in Christ.

The Feast and the Wedding Supper

Isaiah 25 pictures a great banquet on God’s mountain, where death will be swallowed up forever. Revelation 19 presents the marriage supper of the Lamb, where the faithful rejoice in the final victory of God. The table is set with Isaiah’s promises, and Revelation invites us to take a seat.

Why John Leans on the Old Testament

Why does John root his vision in Daniel, Ezekiel, and Isaiah?

Continuity of God’s Story – Revelation is not a new plan. It’s the unfolding of the same promises God gave through the prophets.

Authority for the Church – By using prophetic imagery, John reminds the churches that they stand in line with God’s people across history. Their suffering fits into a larger story.

Imagination That Shapes Faith – The Old Testament provided a visual, poetic language that helps the church see beyond Rome’s power to God’s reign.

Revelation is the last chapter of the Bible not because it’s the latest but because it ties the whole story together.

Old Testament Imagery in Revelation: Meaning for Today

For us, the Old Testament imagery does two things.

First, it grounds our faith. Revelation is not the dream of one man on an island—it is the echo of generations of God’s prophets. When we see Daniel’s Son of Man, Ezekiel’s temple, and Isaiah’s new creation, we realize that Revelation is not a detached apocalypse but a faithful continuation.

Second, it invites us to read the Bible as one story. Too often we separate Old Testament and New. Revelation won’t let us. It insists that the promises made are the promises kept.

Daniel’s beasts remind us that empires still rise and fall. Ezekiel’s temple reminds us that God still dwells with his people. Isaiah’s new creation reminds us that hope is still ahead.

Revelation gathers it all and tells us: the Lamb is on the throne.

And it ends before you expect it to.

Frequently Asked Questions About Old Testament Imagery in Revelation

Why does Revelation use so much Old Testament imagery?

John uses Old Testament visions to show that God’s promises are fulfilled in Christ. It connects the early church to God’s larger story.

Which Old Testament book is most referenced in Revelation?

Daniel is the most direct influence, especially with its visions of beasts, thrones, and the Son of Man. Ezekiel and Isaiah follow closely.

What does Daniel contribute to Revelation?

Daniel provides the vision of beasts, the Ancient of Days, and the Son of Man—all of which resurface in John’s visions.

How does Ezekiel shape Revelation?

Ezekiel contributes temple imagery, the scroll eaten by the prophet, and the river of life—all echoed in Revelation’s visions.

Where does Isaiah appear in Revelation?

Revelation uses Isaiah’s oracles against Babylon for its vision of Rome’s fall and echoes Isaiah’s hope of new creation in Revelation 21–22.