Who Wrote Isaiah?

Introduction

Few biblical books loom as large as Isaiah. Quoted frequently in the New Testament, saturated with poetry, and marked by soaring theological vision, Isaiah has shaped Jewish and Christian imagination for centuries. Yet careful readers notice something striking: the book shifts tone, historical setting, and audience in ways that raise real questions about authorship.

Understanding who wrote Isaiah matters because it directly addresses one of the most common faith concerns modern readers face: how can a book shaped over time still be inspired by God? Isaiah provides one of the clearest biblical answers.

Isaiah Son of Amoz: The Foundational Prophet

The opening verse anchors the book historically:

“The vision of Isaiah son of Amoz, which he saw concerning Judah and Jerusalem in the days of Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah, kings of Judah.” (Isaiah 1:1, NRSV)

This superscription situates Isaiah son of Amoz in the eighth century BCE, during the Assyrian crisis. Passages throughout Isaiah 1–39 reflect this historical setting, addressing Jerusalem, Judah, and threats from Assyria (Isaiah 7; Isaiah 36–37).

John J. Collins notes that these chapters bear clear marks of eighth-century prophetic preaching, including court politics, warnings of judgment, and calls to trust God rather than foreign alliances (Collins, Introduction to the Hebrew Bible, pp. 356–360).

Most scholars agree that Isaiah son of Amoz stands behind substantial portions of Isaiah 1–39, even while recognizing later editorial shaping.

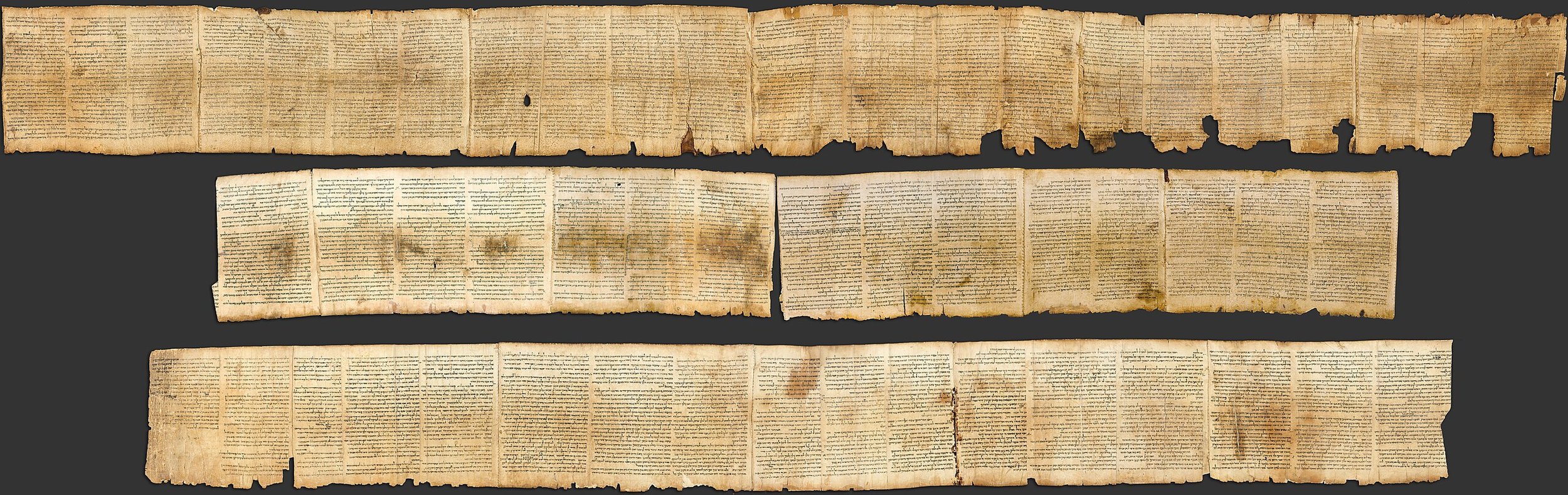

This is the Great Isaiah Scroll found in the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Source

Shifts Within the Book of Isaiah

Beginning in Isaiah 40, the book’s horizon changes dramatically:

“Comfort, O comfort my people, says your God.” (Isaiah 40:1, NRSV)

Here the audience is no longer pre-exilic Judah but a people already in exile. Babylon, not Assyria, becomes the dominant power (Isaiah 43:14). Cyrus of Persia is named explicitly as God’s agent (Isaiah 44:28; 45:1), a figure who lived nearly two centuries after Isaiah son of Amoz.

These historical references strongly suggest that later prophets contributed to the book. Brevard S. Childs argues that this does not represent fragmentation but faithful transmission, as Isaiah’s message was reapplied to new historical moments (Isaiah, Old Testament Library, pp. 3–8).

Prophetic Continuity and Expansion

Most scholars describe Isaiah as developing in stages:

Isaiah 1–39: rooted in the eighth century BCE

Isaiah 40–55: addressing the Babylonian exile

Isaiah 56–66: reflecting postexilic realities

Rather than separate books stitched together, these sections display theological continuity. Themes of holiness, justice, trust, and restoration recur throughout. The later sections do not abandon Isaiah’s message but extend it.

Walter Brueggemann emphasizes that the prophetic imagination of Isaiah becomes a shared inheritance, carried forward by disciples who remained faithful to the original vision while addressing new circumstances (Isaiah 1–39, pp. 1–6).

Evidence Within the Text Itself

Isaiah openly acknowledges the preservation and transmission of prophetic words:

“Bind up the testimony, seal the teaching among my disciples.” (Isaiah 8:16, NRSV)

This verse suggests an ongoing community of interpretation rather than a single isolated voice. It anticipates that Isaiah’s message would be preserved, taught, and reapplied.

Later chapters continue to speak in the same theological register while addressing different audiences:

“I am about to do a new thing; now it springs forth, do you not perceive it?” (Isaiah 43:19, NRSV)

The prophetic voice remains consistent even as history changes.

Inspiration and Multiple Authorship

The book of Isaiah offers one of the Bible’s clearest examples of how inspiration operates across time. God’s word is not frozen in a single moment but speaks again through faithful interpreters.

Brevard Childs argues that the final form of Isaiah is itself the inspired text, preserving prophetic testimony shaped for successive generations (Introduction to the Old Testament as Scripture, pp. 325–331).

This view allows readers to affirm both historical development and theological authority without tension.

When Was Isaiah Written?

The material within Isaiah spans roughly from the eighth to the fifth century BCE. The book’s final form likely emerged in the postexilic period, when earlier prophetic material was gathered and shaped into the coherent work preserved in Scripture.

This long formation explains Isaiah’s remarkable depth. The book speaks across judgment, exile, and hope, holding them together within a single prophetic vision.

Why Authorship Matters

Understanding who wrote Isaiah helps readers see how Scripture addresses real historical change. Isaiah shows that faithfulness includes remembering, reinterpreting, and re-proclaiming God’s word in new circumstances.

The book invites readers to trust that God’s voice is not diminished by time, editing, or expansion. Instead, it is clarified.

Isaiah stands as a testimony that inspiration works through communities, tradition, and faithful imagination.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did Isaiah son of Amoz write the entire book?

Isaiah son of Amoz authored much of the earliest material, but later prophetic followers contributed to the book’s final form.

Why does Isaiah name Cyrus?

The reference reflects later prophetic proclamation during the exile, extending Isaiah’s theology into a new historical moment.

Does multiple authorship undermine prophecy?

No. Isaiah demonstrates how prophecy can be preserved, expanded, and reapplied while remaining authoritative.

Is Isaiah one book or several?

Isaiah is one book formed through a long prophetic tradition rather than separate unrelated works.

Sources and Further Reading

Collins, John J. Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. 3rd ed. Fortress Press, 2018, pp. 355–372.

Childs, Brevard S. Isaiah. Old Testament Library. Westminster John Knox Press, 2001, pp. 1–20.

Brueggemann, Walter. Isaiah 1–39. Westminster John Knox Press, 1998, pp. 1–12.